My first encounter with veteran Los Angeles anchor Alex Cohen was watching her interview Jill Abramson, the former executive editor of the New York Times. Abramson was in town promoting her book and she clearly was used to fawning questions because of her once vaunted status. Unfortunately, Cohen had taken the time to read Abramson’s book and she knew the controversies surrounding the former editor, including allegations of plagiarism. Let’s just say I left the event a lot more impressed with Cohen than I was with Abramson.

It wasn’t Cohen’s intent to embarrass or undermine Abramson. In fact, Cohen couldn’t have been nicer or more gracious. Perhaps Abramson was quite the journalist in her day, but she couldn’t offer meaningful answers to Cohen’s substantive questions. Fortunately for Abramson, Cohen was so gentle that I doubt the former Times editor realized her answers left audience members wondering how she ever rose to such an influential position.

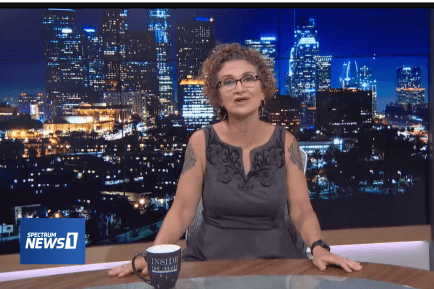

I rediscovered Cohen last month when I turned on my television to watch Larry David’s Curb Your Enthusiasm for some isolation relief. Spectrum, my cable provider, defaults my TV to its local cable channel and Cohen, who hosts a show called Inside the Issues, had just begun interviewing Dr. Aaron Weinberg, a Pulmonologist at Cedars-Sinai. I learned quite a bit about the novel coronavirus and was heartened that a doctor of Weinberg’s obvious caliber practices medicine at the hospital closest to my home.

I’ve since watched about a dozen more interviews that Cohen has conducted. In the more than three decades I’ve spent in journalism and public relations, I’ve only encountered two persons with Cohen’s superior deftness putting interview subjects at ease and eliciting information from them. One was Barbara Frum, a former host of As It Happens on Canada’s CBC radio network; the other is Diane Brady, formerly of Business Week and the Wall Street Journal. Brady also hails from Canada, which is where many prominent U.S. journalists began their careers. The famed politeness that once distinguished Canadians made them better listeners, in turn making them better journalists.

What awes me about Cohen is her unassuming but genuine warmth and her unwavering practice keeping the focus on her guests, rather than treating them as foils to showcase her own intelligence and opinions. Cohen, 48, asks probing questions intended to draw out the expertise of her guests. She lets them talk at length and rarely interrupts. As best I can tell, Cohen doesn’t rely on producers feeding her questions through an earpiece because her questions are too spontaneous.

Cohen, a former host and reporter for NPR’s All Things Considered in Los Angeles and other network programs, is such an extraordinary talent that even when she filmed getting a tattoo on her back, she managed to keep the focus on the artist applying the ink rather than call attention to the pain or discomfort she was experiencing. The tattoo segment didn’t strike me as a publicity stunt but rather an attempt to share with viewers something highly personal. Cohen revealed at the outset of the segment that she got her first tattoo at 17 and removed her jacket to reveal sizeable tattoos on both her arms.

Cohen’s tattoos are hardly a surprise given another detail about her life and pursuits. From 2003 until 2010 she was a member of the Los Angeles Derby Dolls, an all-female banked track roller derby league where she was known as “Axles of Evil.” Cohen served as a consultant for the Drew Barrymore-directed 2009 roller derby film Whip It where she taught the cast how to scrimmage and take a fall. This Wall Street Journal article provides insights about Cohen’s roller derby career and the origins of “Axles of Evil.”

Cohen’s background reaffirms a lesson I learned from my former world champion kickboxing instructor Charlie “The Cream” Cassis: Genuinely tough people keep that side of themselves hidden. I once commented to Cassis that if I had his kickboxing talents, I’d waste anyone who so much as looked at me the wrong way. Cassis replied that knowing he could demolish someone gave him the strength and courage to avoid and walk away from conflicts. Like Cohen, Cassis’s outer persona was that of gentle soul.

Cohen also reaffirms my belief that local news can only succeed if its overwhelmingly overseen and covered by people with longstanding ties or commitments to the communities they cover. Cohen has spent virtually her entire life in California, and she knows and understands Angeleno culture and mores. That knowledge and background is apparent in her interviews.

The novel coronavirus has revealed that many television “news” personalities aren’t up to the task of covering a global pandemic. NBC’s Chuck Todd asking Joe Biden whether Donald Trump has “blood on his hands” was so inappropriately over the top that even the former vice president said the comment was “a little too harsh.” Todd conveniently neglected to ask Biden about his earlier criticisms of Trump’s China travel ban, a move that Dr. Anthony Fauci has credited with saving lives.

NBC’s Peter Alexander garnered attention for himself asking Trump an inane question that was intended to antagonize the president. Even the normally mild-mannered Dr. Fauci has on occasion become visibly frustrated with the accusatory questions White House reporters have posed to him; he also took CNN’s Jim Acosta to task for posting soundbites taken out of context.

Grandstanding by White House reporters has been going on for decades. “Reporters ask questions not to get information, but to get a reaction,” former White House correspondent Susan Milligan admitted in a 2015 Columbia Journalism Review article. But in these troubled times the public has grown tired of the “made for TV and social media” antics.

A Gallup survey last week revealed the majority of the public disapproves of the media’s coverage of the coronavirus. I’m doubtful survey respondents were referring to the heroic coronavirus coverage of the Washington Post and the Wall Street Journal but rather the posers occupying the White House briefing room and the network anchor chairs.

Americans can’t afford to entrust coverage of the coronavirus pandemic to corporate owned entertainment companies looking to incite drama and conflict to fuel the prejudices of their respective audiences. These times require real-deal television journalists like Alex Cohen who has the talent, temperament, and temerity to engage Donald Trump and expose truths about the president that would be undeniable even to his longtime supporters. As was true with Jill Abramson of the New York Times, the president won’t even know what hit him.