Forty years have passed since I briefly crossed paths with Rosie DiManno, but my memory of her is quite vivid.

DiManno was a rookie reporter assigned to a suburban bureau of the Toronto Star when I was a business reporter at the newspaper in the early 80s. DiManno didn’t come to the downtown newsroom often, but when she did, everyone took notice. DiManno was partial to wearing in-your-face outfits like the revealing sundress she showed up in one day and brought the newsroom to a near standstill. There was an unmistakable “Fuck You” about DiManno’s style and manner. I admired her defiance.

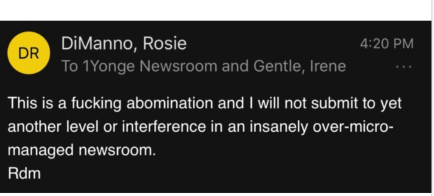

I recently learned DiManno, 62, went on to become a Star columnist and one of the newspaper’s most popular writers. DiManno clearly hasn’t mellowed with age, as evidenced by the newsroom-wide email she sent out after the Star last summer announced an internal ombudsman to ensure a “safe place” for black, indigenous, and people of color journalists.

DiManno’s email sparked an uproar, with more than five dozen newsroom employees signing a petition demanding that she attend “anti-racism training” and be forced to “apologize to the newsroom and demonstrate an understanding of why these measures are necessary.” As best I can tell, DiManno held her ground and refused to be reprogrammed.

DiManno is possibly the last remaining legacy of a bygone Toronto Star era when she would have been in good company deriding the appointment of an editor responsible for leading newsroom renditions of “Kumbaya.” There was no “safe place” at the Toronto Star I remember so fondly.

Working at the newspaper was far-and-away the best and most rewarding job I ever had, though admittedly I didn’t know it at the time. That’s because I lived in a constant state of fear holding my own among what was then home to Canada’s top and most richly compensated journalists. The Star was an intense, competitive place where reporters were only as good as their last stories.

Sadly, the Star has fallen on hard times. Its circulation is down more than 25 percent from its peak, and the Honderich and other families who controlled the newspaper for decades and admirably kept it true to its founding liberal ideals last May surrendered control to a Bay Street financier. As for the public respect the Star once commanded, someone tweeted about the newsroom petition against DiManno, “Where did they find 62 journalists at the Star?”

In its day, the Star was unquestionably one of the best and most successful local newspapers in North America, if not the best. Its circulation was more than double that of its two Toronto rivals, and the newspaper was awash with money. Reporters were paid overtime for working more than 40 hours a week; triple time for working Christmas and New Year’s. I couldn’t believe I got paid so much money for doing something I would have been willing to do for a fraction of my salary.

The Star’s earlier success was predicated on a simple formula: “What’s it Mean to Metro?” Metro referred to the five boroughs that comprised Metropolitan Toronto, and the newsworthiness of every story was weighed against its relevance to the city’s residents. The Star required a local angle even on international stories. Legend has it that the Star once ran a headline, “Cousin of Metro Family Among Victims in India Plane Crash.”

Toronto’s then dominant WASP community read the Globe and Mail, but the city’s fast growing immigrant population gravitated to the Star. It was a truly liberal paper, governed by the so-called Atkinson Principles outlined by its famed publisher Joseph Atkinson more than a century ago. These principles included a strong, united and independent Canada, social justice, individual and civil liberties, community and civic engagement, the rights of working people, and the necessary role of government.

The Star was promoting women, minorities, and people with disabilities long before it was fashionable. In 1970, it assigned Sally Barnes to cover the Ontario legislature, known as Queen’s Park. (FYI: A one-hour conversation with Barnes inspired me to pursue a career in journalism and she was instrumental in my getting hired at the Star.) A few years later, the Star promoted Martin Goodman as the newspaper’s managing editor; in those days it was rare for a Jewish person to hold a top position at a Canadian newspaper, or any major Canadian company for that matter, except real estate and retail concerns.

When I worked at the Star the city editor – the most critical newsroom position and the one overseeing the biggest staff – was a woman, as were half the section heads. The Star’s Ottawa columnist was a woman, the editorial page editor was from India, and there was a black reporter assigned to cover Toronto’s burgeoning Caribbean community. Michele Landsberg, then one of Canada’s preeminent feminist writers and social activists, wrote a column. The Sunday business editor had MS and the real estate section’s photographer had one arm. Unlike its rivals, the Star was chock full of bylines with ethnic names.

The Star understood Toronto and had a deep connection with its readers. You want to talk about engagement? When my father would bring the Star’s final afternoon edition home upon returning from work, my mother would stop preparing dinner to read Gary Lautens, the Star’s resident humorist. She then insisted on the family listening to her read the column aloud as a condition to being served dinner. Hard to believe, but newspapers once employed columnists whose mandate was to make readers laugh and feel good. As an aside, Lautens years later was named editor of the paper, a job he neither solicited nor wanted.

The Star editors I worked with were the best I encountered in my journalism career. As I covered the Greymac affair, still one of the biggest business scandals in Canadian history, I got to work closely with then managing editor Ray Timson, who those in the know will readily agree was Canada’s best journalist of all time. Timson made an international name for himself when he successfully tracked down Gerda Munsinger, a socialite believed to be a Soviet spy who slept with influential Canadian Cabinet ministers and then suddenly disappeared. Though rumored to have died, Timson and a colleague found her in a Munich apartment and scored a major interview.

Timson fit the image of a swashbuckling journalist, but he was a quiet sort, at least during my encounters with him. He commanded great respect and even the Star’s most experienced and accomplished editors wouldn’t dare challenge him.

At a meeting with Timson after I first broke the Greymac scandal, editors enthusiastically presented more than a dozen follow up stories they had in the works, hoping to impress him with their expansive initiatives. After hearing all the pitches, Timson advised the scandal was of the magnitude that it would take months to understand and analyze. On the back of an envelope from the stack of mail he just picked up, Timson wrote down five questions that he said the Star must answer for its readers in descending order. The envelope served as the framework for the Star’s coverage and dozens of exclusive stories.

Timson was tough, but he was fair and over time I learned he also was quite kind. The Star’s front page was posted outside the newsroom mailroom and one day Timson noticed a slew of damning anonymous quotes about various individuals. He promptly issued an edict that going forward anonymous quotes would no longer be allowed, except under very special circumstances. In the Star’s first written code of conduct, Timson added these sentences: “The Star does not provide anonymity to those who attack individuals or organizations or engage in speculation — the unattributed cheap shot. People under attack in the Star have the right to know their accusers.”

There was a dark side to working at the Star, one that kept editors and reporters constantly on edge and pitted against each other. It was an insanely competitive place, and if a reporter got beat a few times by the rival Globe and Mail, the Toronto Sun, or any other publication, they would be promptly reassigned. The greatest competition often came from within.

After weeks of covering the Greymac affair and having my stories routinely appear on page one, a columnist/reporter in the business section figured out one of my sources and called him representing that she was doing so at my suggestion. He gave her a huge scoop he intended for me and she ran with it. I was livid and figured she’d be promptly fired when I ratted her out for her deception.

John Honderich was the editor I reported to on the Greymac story. Although he was the son of the publisher and destined to succeed his father, Honderich had a law degree and was widely well regarded for his intellect and journalism chops. He didn’t react to my colleague’s deception as I expected.

“I think this is great,” Honderich said with a smile as wide as Toronto’s 401 Freeway. He went on to explain that the Greymac story wasn’t mine, but the Star’s, and the newspaper welcomed internal competition to ensure it was always first in covering the scandal.

Honderich also educated me on the the Star’s formula for success. He said it was predicated on attracting and tolerating people with diverse backgrounds, beliefs, and personalities, including “intense” people like myself. Honderich said that if I had an issue with the reporter who surreptitiously scooped me, I’d have to fight my own battles.

I left the Star because my ego got in the way. After months of covering a major scandal and temporarily reporting directly to Timson and Honderich, when the controversy ended, I had to return to the business section and resume doing mundane stories, like corporate earnings and the stock market wrap up. That was a Star tradition; when a reporter had a good run and began achieving a semblance of stardom, they were cut down to size and reminded the Star made them great, not the other way around. When Timson learned I had resigned, he told me that I was weeks away for getting promoted to cover Queen’s Park.

I went on to work for other major newspapers in Canada and the U.S., but I never again experienced the pride and satisfaction I felt working at the Star. Sure, working there often wasn’t pleasant, and at times I felt betrayed. But the negative experiences were outweighed by the positive ones like working with talents like Timson, Honderich, my business editors Helen Henderson and Cosentino De Giusti, and a slew of other top notch journalists.

That’s why I pity woke reporters like the ones who wanted DiManno disciplined. They are part of a new breed of journalists focused on promoting their brands and their values at the expense of the publications that employ them. They don’t respect their editors, rightly so given how their bosses fear and indulge them. They will never know the humility I experienced attending meetings with an accomplished editor with decades of experience like Ray Timson or the thrill of being part of a world-class organization they regard as much greater than themselves. Their professional memories will be losing readers and getting people cancelled.

One can potentially argue that making journalism a kinder and gentler place to work is progress, but the evidence suggests that North American journalism is on an irreversible decline. Nearly 50 percent of Canadians don’t trust the media, on par with American distrust. The wokesters at the Star should be asking themselves why DiManno is so popular with readers if she is as racist as they claim. Canada is among the most woke countries on the planet.

The greatest moment of my professional career was when Timson invited me to join him for drinks at the ground floor bar in the Star building. Timson didn’t fraternize with reporters and typically when someone resigned from the Star, they became an instant newsroom pariah. The Star would never rehire someone who quit.

After consuming six or more beers, I gathered the courage to ask Timson a question that was long on my mind. Despite his stature and accomplishments, Timson himself was promoted and demoted multiple times during his tenure at the Star.

I asked Timson why he withstood the humiliation. Without missing a beat, he looked at me with his inimitable intense stare and said, “It builds character.”

Something woke journalists might want to consider the next time things don’t go their way.